In January 2017, results arrived. I was accepted at the LSE, a system laboratory in my school. We were 4, and had to find a new project to work on. One wanted to work on the linux kernel security, another on Valgrind, and then, there is me. I didn’t knew how to start, but I wanted to work on something related to GPUs.

My teacher arrived, and explained the current problem with Windows and QEMU: we don’t have any hardware acceleration. Might be useful to do something about it ! I was not ready…

The first step was to understand Linux graphic stack, and then find out how Windows could have done it. Finally, how we can bring this together using Virgl3D and VirtIO queues.

This article will try present you a rapid overview of the graphic stack on Linux. There already is some pretty good articles about the userland part, so I won’t focus on that, and put some links.

OpenGL 101

Let’s begin with a simple OpenGL application:

int main(int argc, char** argv)

{

glutInit(&argc, argv);

glutInitWindowSize(300, 300);

glutCreateWindow("Hello world :D");

glClear(GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT);

glBegin(GL_TRIANGLE);

glVertex3f(0.0, 0.0, 0.0);

glVertex3f(0.5, 0.0, 0.0);

glVertex3f(0.0, 0.5, 0.0);

glEnd();

glFlush();

return 0;

}

This is a non working dummy sample, for the idea

As we can see, there is three main steps:

- Get a window

- Prepare our vertices, data…

- Render

But how can we do that ?

Linux graphic stack

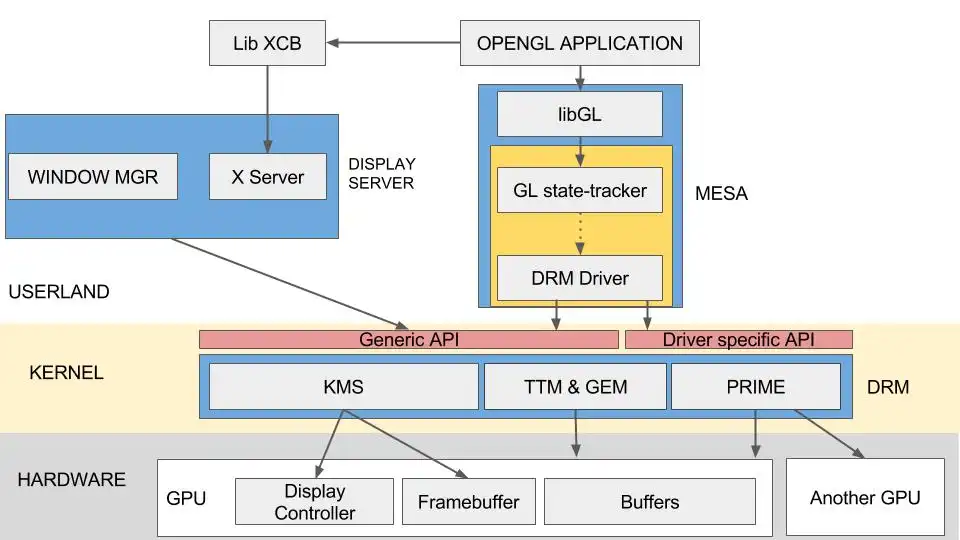

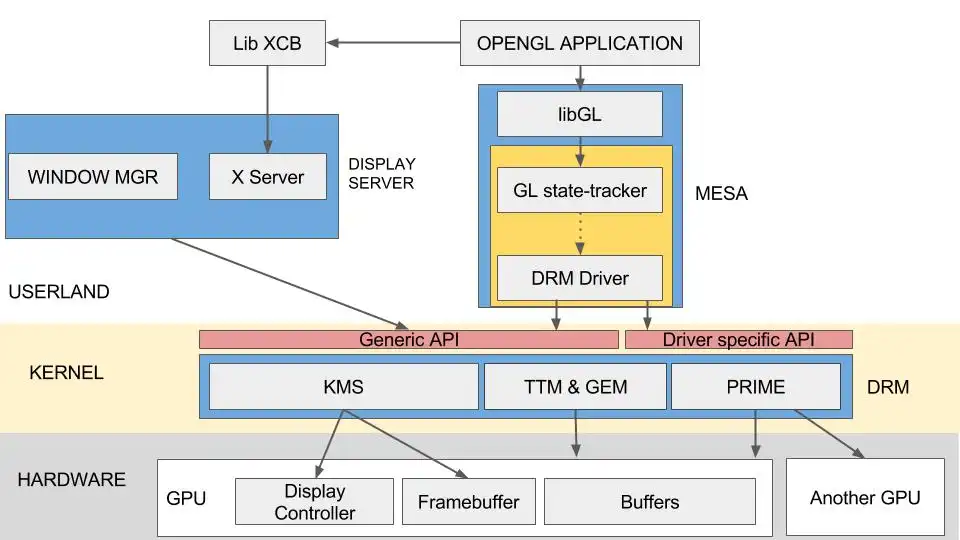

Level 1: Userland, X and libGL

The first part of our code looked like this:

glutInit(&argc, argv);

glutInitDisplayMode(GLUT_SINGLE);

glutInitWindowSize(300, 300);

glutInitWindowPosition(100, 100);

But in fact, actions can be resumed to something like this:

CTX = glCreateContext()

CONNECTION = xcb_connect()

xcb_create_window(CONNECTION, PARAMS, SURFACE, WINDOW)

What ? a connection, a context ?

To manage our display, Linux can use several programs. A well known is the X server. Since it’s a real server, we have to connect to it first before being able to request anything. To ease our work, we will use the lib XCB. Once a window is created, any desktop manager compatible with X will be able to display it. For more informations about an OpenGL context -> Khronos wiki

Meet Mesa

Mesa is an implementation of OpenGL on Linux. Our entry point is libGL, just a dynamic library letting us interface with the openGL runtime. The idea is the following:

- libGL is used by an OpenGL application to interact with Mesa

- Generic OpenGL state tracker. Shaders are compiled to TGSI and optimized

- GPU layer : A translation layer specific to our graphic chipset

-

libDRM and WinSys: an API specific to the kernel, used interface with the DRM

-

OpenGL state tracker: from basic commands like GlBegin GlVertex3 and so on, Mesa will be able to generate real calls, to create command buffers, vertex buffers, etc… Shaders will be compiled into an intermediate representation: TGSI. A first batch of optimizations in done on this step.

-

GPU layer: We now need to translate TGSI shaders to something our GPU can understand, real instructions. We will also shape our commands for a specific chipset.

- libDRM and WinSys: We send this data to the kernel, using this interface

With this architecture, if I want to add a support to my own graphic card, I will have to replace one part : the GPU layer

For more informations about Mesa and Gallium -> Wikipedia Another good article on the userland part -> Igalia blog

Welcome to KernelLand !

Meet the DRM

DRM: Direct Rendering Manager. This is more or less an IOCTL API composed of several modules. Each driver can add some specific entry points, but there is a common API designed to provide a minimal support. Two modules will be described: KMS and the infamous couple TTM & GEM.

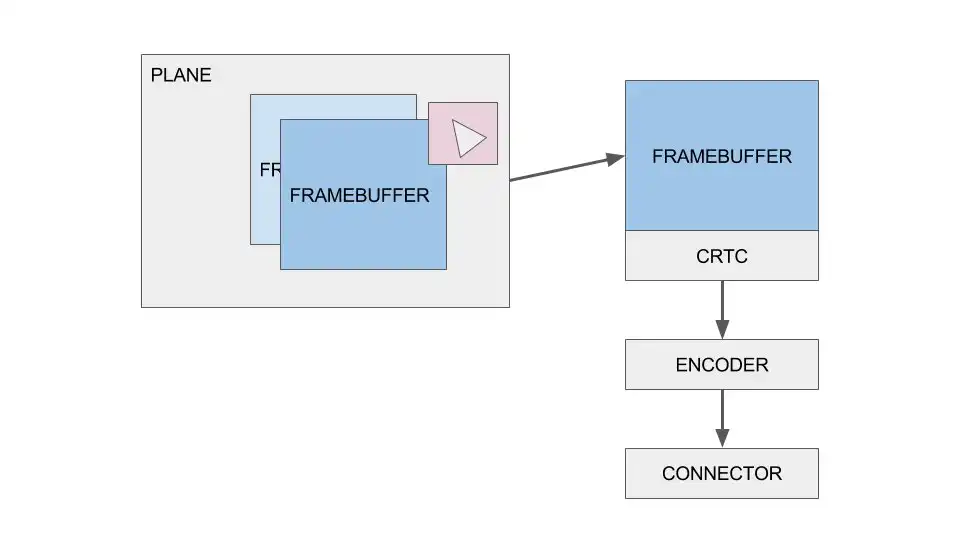

Meet KMS

Remember the first step of our OpenGL application ? Ask for a window, getting a place to put some fancy pixels ? That’s the job of the KMS: Kernel Mode-setting.

A long time ago, we used UMS: user mode setting. The idea was to manage our hardware directly from userland. Problems: every application needed to support all the devices. It means a lot of code was written, again and again. And what if two applications wanted to access to the same resources ? So, KMS. But why ?

Framebuffer: a buffer in memory, designed to store pixels

The story begins with a plane. Picture it like a group of resources used to create a image. A plane can contains several framebuffers. A big one, to store the full picture, and maybe a small one, something like 64x64 for an hardware cursor ? These framebuffers can be mixed together on the hardware to generate a final framebuffer.

Now, we have a buffer storing our picture. We assigned it to a CRTC (Cathode Ray Tube Controller). A CRTC is directly linked to an ouput. It means if your card has two CRTCs, you can have two different output. Final step, printing something on the screen. A screen is connected using a standard port, HDMI, DVI, VGA… this means encoding our stream to a well defined protocol. That’s it, we have some pixels on our screen !

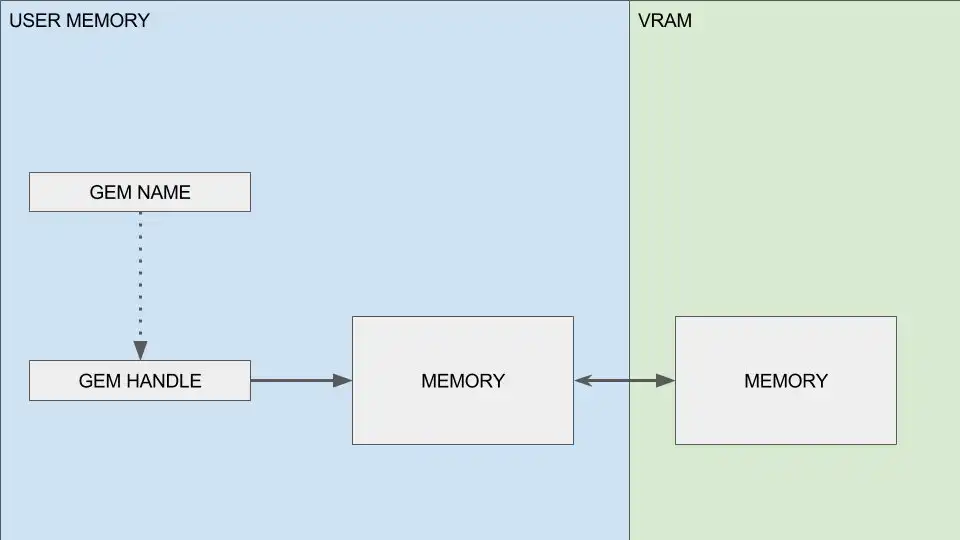

TTM & GEM

We can print some pixels, great ! But how can we do some fancy 3D stuff ? We have our GL calls going through some mumbo-jumbo stuff, and then what ? How can I actually write something on my GPU’s memory ?

There globally two kind of memory architecture: UMA and dedicated

- UMA for Unified Memory Access, is used by Intel Graphics, or on some Android devices. All your memory is accessible from one memory space.

- Dedicated memory: You can’t directly access your memory from the CPU.If you want to write it, you have to map a CPU addressable area, write your data, and then, use specific mechanisms to send it on the dedicated memory.

TTM and GEM are two different APIs designed to manage this. TTM is the old one, designed to covering every possible cases. The result is a big and complex interface no sane developer would use. Around 2008, GEM was introduced. A new and lighter API, designed to manage UMA architectures. Nowadays, GEM is often used as a frontend, but when dedicated memory management is needed, TTM is used as backend.

GEM for dummies

The main idea is to link a resource to a GEM handle. Now you only need to tell when a GEM is needed, and memory will be moved on and out our vram. But there is a small problem. To share resources, GEM uses global identifiers. A GEM is linked to a unique, global identifier. This means any program could ask for a specific GEM and get access to the resource… any.

Gladly, we have DMA-BUF. The idea is to link a buffer to a file descriptor. We add some functions to convert a local GEM identifier to a fd, and can safely share our resources.

I’ll stop here for now, but I invite you to check some articles on DMA (Direct memory access) and read this article about TTM & GEM